Increasing the EQ of AI

Why talking about the “E” word is critical in AI

Matthew Hutson is a contributing writer at The New Yorker and a former news editor for Psychology Today.

Why talking about the “E” word is critical in AI

Matthew Hutson is a contributing writer at The New Yorker and a former news editor for Psychology Today.

Rana el Kaliouby is the co-founder and CEO of Affectiva. Photo source: Rana el Kaliouby

Last year, Rana el Kaliouby was preparing to go on a tour to promote her new book, Girl Decoded, a memoir about growing up in Egypt, studying computer science, joining the MIT Media Lab, and starting a successful tech company. El Kaliouby has an energetic presence. She enjoys public speaking and was looking forward to bringing her story to a larger audience.

“But then, you know, COVID happened.”

She took her tour online. She streamed fireside chats but couldn’t see the faces of her viewers. “It’s a painful experience,” she says, “because that emotional connection with your audience broken.”

What was ironic is that her book talks about this exact phenomenon. El Kaliouby co-founded Affectiva to bring emotional intelligence to artificial intelligence, primarily by inferring emotions from faces.

The technology, which is part of a growing field called affective computing, or emotion AI, has applications in areas as diverse as videoconferencing, social robotics, customer service, therapy chatbots, tutoring software, and market research.

“When we talk about artificial intelligence, for the most part the rhetoric is about cognitive abilities such as problem-solving,” el Kaliouby told me when we first spoke in 2016 for an article in The Atlantic.

However, emotion is a vital part of cognition. People with damage to parts of the brain responsible for emotional processing have trouble making even the most basic decisions. They don’t evolve into cool and logical versions of Spock, a character on the television show Star Trek whose actions were ruled by logic rather than emotion. On the contrary, they can spend entire afternoons trying to perform the simplest of tasks, like categorizing documents at work.

Back in 2016, el Kaliouby told me, “When it comes to generalized AI, these systems need to have emotion AI as well. We see it as a must-have, not a nice-to-have.”

Recognizing emotions from faces

El Kaliouby was born in 1978 in Kuwait, where her parents had jobs working with computers. The family returned to Egypt at the start of the Gulf War in 1990. She studied computer science at the American University in Cairo (AUC) and graduated at the top of a class of 300 people at age 19 (she skipped grades 1 and 8).

El Kaliouby stayed on at AUC for a master’s degree. She intuited the need for better human-computer interactions, and her then boyfriend (later husband), tech entrepreneur Wael Amin, recommended a 1997 book by MIT computer scientist Rosalind Picard, Affective Computing. She was inspired by Picard’s thesis that computers must learn to recognize and understand human emotion if truly intelligent computing could ever be achieved.

But where to begin? El Kaliouby decided to develop a program that could recognize facial expressions of emotion.

For her master’s thesis, she created an algorithm that could point to facial landmarks in videos, such as the eyes and nose, and track them—a crucial first step in the analysis of facial expressions and emotion detection. To go further, however, el Kaliouby felt she needed a PhD. She enrolled in a program at the University of Cambridge, where she developed her “Mind Reader” algorithm to recognize emotional expressions—just in time for a visit by Picard to the lab.

Picard asked her on the spot to do a postdoctoral fellowship at MIT after her PhD. However, el Kaliouby had already planned to return to her husband and family in Cairo and take up a teaching post at AUC. Picard would not take no for an answer, however, and within a year el Kaliouby joined Picard at MIT.

The birth of emotion AI

Having previously worked in risk-averse environments, el Kaliouby experienced a significant culture shock when she joined MIT’s Media Lab. In contrast to the more conservative academic and professional environments that had shaped her career, people were rewarded for failing spectacularly at MIT.

She loved it.

With Picard, she developed the next version of Mind Reader, FaceSense. They loaded it onto a tablet connected to Bluetooth headphones and a miniature camera on a pair of glasses. A person wearing the device could look at you and hear a voice labeling the emotion on your face. The product was especially appropriate for people with autism, who often have trouble reading social cues.

The system, iSET, was a precursor to augmented reality headsets like Google Glass. When the lab’s sponsors visited, they loved FaceSense. They pictured many possibilities for the product that ranged from detecting drowsy drivers to gauging consumer reactions to a product or service.

Picard and el Kaliouby decided to spin their work out into a company. In 2009, they founded Affectiva.

Affectiva’s system uses a kind of artificial intelligence called machine learning. Scientists feed an algorithm labeled data, such as video frames that experts have laboriously annotated with data about emotional cues. Over time, the algorithm learns to predict those annotations on its own. In 2015, el Kaliouby rewrote the software to draw on advancements in deep learning, a subset of machine learning where artificial neural networks loosely mimic the workings of the human brain.

That same year, el Kaliouby gave a talk at TEDWomen. Her talk has since been viewed nearly two million times. When she and Picard visited venture capital firms, they talked about affect, valence, or sentiment, but not emotion—“we just avoided the E word,” she says, so as not to sound soft and unscientific in front of men. After the talk, “I was like, ‘I’m totally gonna own this whole emotion thing,’” she says. They started using the term emotion AI for their work. Soon after, el Kaliouby felt the need to take the reins of the company she co-founded, and she became CEO in 2016.

Parkinson’s, Pepper, and beyond

Since its founding, Affectiva has partnered with companies like CBS Entertainment Group, Mars, and Giphy. The company also partners with researchers who want to explore applications for their technology—from evaluating smiles after facial reconstructive surgery, diagnosing Parkinson’s disease, and providing performance feedback to practicing giving talks at home. Affectiva’s other big market is driver analysis, detecting when people are sleepy, distracted, or feeling emotionally out of sorts.

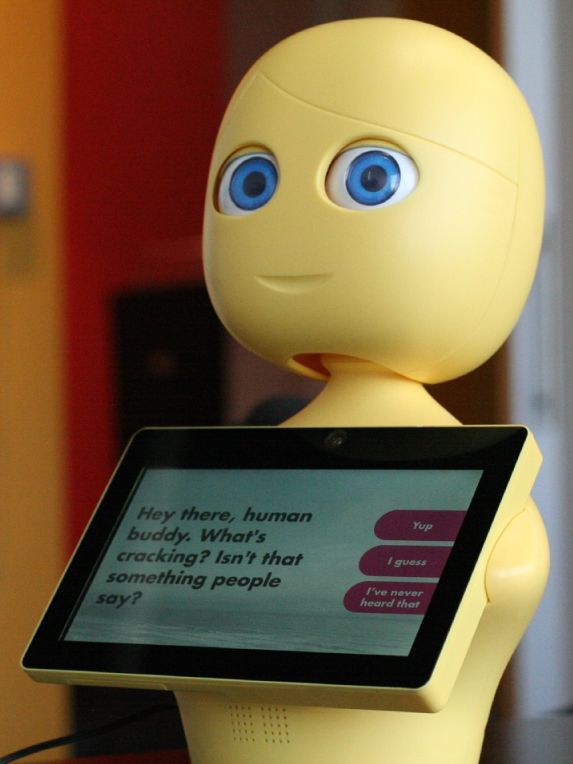

Emotion Al also has clear uses in social robotics. Pepper is a four-foot-tall humanoid robot on motorized wheels created by SoftBank Robotics. Thousands of Pepper robots offer information to people at banks, hospitals, museums, and schools. Affectiva is working with SoftBank to help Pepper recognize emotional expressions.

Affectiva did not pursue products for people with autism—their investors declared the market too small—but someone else has taken the baton. As soon as Google Glass came out in 2013, cognitive neuroscientist Ned Sahin founded Brain Power. The company offers several software tools to empower children on the autism spectrum. In Girl Decoded, el Kaliouby calls Sahin’s technology a “fulfillment of the mission I began nearly two decades ago: to build an emotion prosthetic for people who needed an EQ boost.”

You can’t recognize emotions from just a face

“When’s the last time you saw someone win an Academy Award for scowling when they were angry or pouting when they were sad?” Lisa Feldman Barrett, a psychologist at Northwestern University, told me in 2014 for an article in Al Jazeera America.

In one paper, she presents a photo of American tennis player Venus Williams screaming in apparent anger or pain, then a zoomed-out version showing Williams pumping her fist. It’s a look of triumph, not agony. To read a face, you need to read the whole scene.

Research conducted by Dr. Paul Ekman suggests that there are six basic emotions: fear, anger, joy, sadness, disgust, and surprise. Barrett told me those six basic emotions are actually constructions in 2007 for an article in Psychology Today. Context is everything. You may interpret physiological arousal as anxiety or excitement or something in between based on your upbringing or how you perceive a particular moment. This explains why a computer might have trouble correctly reading your emotion from an expression, especially when there might not even be a clear-cut emotion to read.

El Kaliouby agrees that context matters: “Unfortunately, it has hurt the field, this simplistic approach of saying there’s six basic emotions, and if you smile, you’re happy.” Much of Affectiva’s work doesn’t try to label people’s emotional states, but merely predicts measurable behavior from facial movement.

So, in a sense, emotion-recognition AI doesn’t recognize emotion. But in another sense, it does. Emotion is about more than conscious experience or a label one puts on one’s feelings. An emotion is a functional bundle of reactions affecting motivation, perception, physiology, expression, reasoning, attention, and behavior.

Describing market researchers who use emotion AI, Jeffrey Cohn, of the University of Pittsburgh, says “they’re not doing it because they have an intense desire to know whether someone’s happy or not. They want to know something about people’s relationship to products. Will they buy the gizmo or not?”

Danger zones

Responsible researchers acknowledge the limitations of emotion AI. Even if emotion AI were to detect emotions perfectly, ethical issues remain. One is the need for consent. Not everyone wants computers (or other people) analyzing their internal states without their knowledge. When el Kaliouby and Picard founded Affectiva, they decided they would not work with partners who couldn’t guarantee the consent of subjects. El Kaliouby even turned down $40 million in funding from a potential partner working in surveillance. There are also risks of manipulation with emotion AI. If machines know how you feel or how to push your buttons, they might make you buy things you don’t need and do it far more effectively than the most compelling advertisement.

To address these challenges, regulatory agencies in Europe have looked into regulating affective computing. Andrew McStay, a professor of digital life at Bangor University in Wales, likes this notion. “Rather than startups trying to deploy in the market and seek forgiveness afterwards,” he says, “the idea would be that you’d have it checked, and you’d have a CE mark, which says that it has passed a safety threshold.”

Rana 3.0

As el Kaliouby’s work has increased the EQ of computers, so too has her own EQ grown. She’s built a business and raised two kids as a single mother in a new country (her marriage didn’t survive the distance), bucking cultural and family tradition. She’s learned to listen to and speak up for her feelings, rather than remain the “nice Egyptian girl.”

In June 2021, Affectiva was purchased by Smart Eye, a company that sells eye-tracking systems for driver monitoring. The purchase price, $73.5 million, is not much more than the amount invested in Affectiva, $62.6 million, an outcome that has raised questions about the readiness of emotion AI for wide-scale deployment.

However, el Kaliouby acknowledges the challenges.

“With the acquisition, obviously, it’s a new chapter for Affectiva, and for me personally,” she says. “But at a high level, I still think this tech category is nascent, and there’s a lot of work to be done. And it’s exciting.”