Four questions with Loral O’Hara: How to file a successful application to the NASA Astronaut Selection Program

The journey into space calls for a catalog of academic and professional accomplishments, as well as some luck.

By Elizabeth Howell

The journey into space calls for a catalog of academic and professional accomplishments, as well as some luck.

By Elizabeth Howell

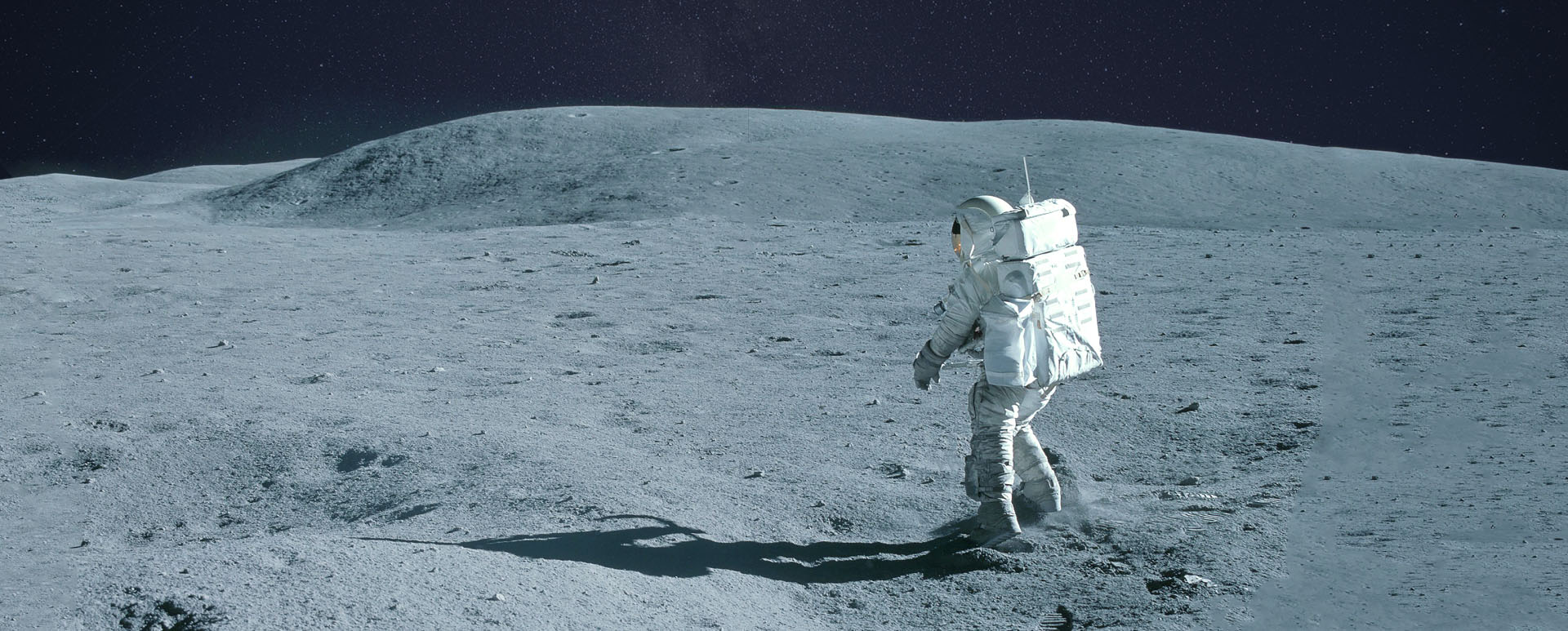

Photo source: Shutterstock

NASA plans to land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon around 2024. Loral O’Hara could be one of the first women to touch down on the surface.

O’Hara was selected by NASA in 2017 and having completed her basic training, she is now eligible for a space mission. She will follow closely in the footsteps of NASA’s Artemis team, which includes nine women, one of whom may be the first woman on the Moon.

NASA generally runs astronaut selections every two years to pick the best Americans for the job. The odds of getting such an opportunity are vanishingly small; the latest astronaut class was announced in December 2021 and includes 10 astronaut candidates from an initial pool of 12,000 applicants. O’Hara’s application round had a success rate of 0.06%, with 11 people selected from a record 18,300 applicants.

The process to apply for an astronaut job varies by your profession. If you’re a civilian, you go through the USAJOBs website; military personnel not only apply on the website but also have to talk with their military service to follow selection procedures there.

NASA then takes roughly 18 months to make a decision on an applicant, including the online application process (screening questions are not disclosed because the agency wants to make the process fair and equitable) and a confidential, multi-round interview, of which outsiders hear very little.

O’Hara was selected by NASA in 2017 and having completed her basic training, she is now eligible for a space mission. She will follow closely in the footsteps of NASA’s Artemis team, which includes nine women, one of whom may be the first woman on the Moon.

NASA generally runs astronaut selections every two years to pick the best Americans for the job. The odds of getting such an opportunity are vanishingly small; the latest astronaut class was announced in December 2021 and includes 10 astronaut candidates from an initial pool of 12,000 applicants. O’Hara’s application round had a success rate of 0.06%, with 11 people selected from a record 18,300 applicants.

The process to apply for an astronaut job varies by your profession. If you’re a civilian, you go through the USAJOBs website; military personnel not only apply on the website but also have to talk with their military service to follow selection procedures there.

NASA then takes roughly 18 months to make a decision on an applicant, including the online application process (screening questions are not disclosed because the agency wants to make the process fair and equitable) and a confidential, multi-round interview, of which outsiders hear very little.

NASA Astronaut Loral O’Hara. Photo Source: Houston Chronicle

In general, NASA’s process includes pulling out a list of highly qualified applicants, verifying everyone’s references, and conducting several rounds of interviews and activities that simulate life as an astronaut and the demands outside of it—such as media interviews.

So how do you stand out from the others? NASA keeps its requirements very broad, in general, only requiring a relevant STEM (science, technology, engineering, or math) degree or some military experience.

But a typical astronaut’s resume has much more than a degree. They have accumulated experience in space-adjacent activities such as piloting, skydiving, or underwater diving. They spend years in what the industry terms “isolated, confined environments.” This can range from working on a ship or joining an expedition to Antarctica—the agency wants to see how one deals with dangerous situations and how one manages working on small teams. A background with government agencies is a huge plus, along with experience teaching the next generation.

Then there is also the luck factor, as astronauts often apply for multiple rounds before being accepted—if it happens at all. If you can’t make it to space, however, NASA has a lot of jobs available for qualified space fans, ranging from roles in mission control to work on its range of planetary missions. You can also pivot into the fast-growing space industry, work as a space educator, or continue as a hobbyist in fields such as astronomy.

O’Hara, however, managed to beat the odds through a combination of luck and experience. She earned a bachelor of science degree in aerospace engineering at the University of Kansas and a master of science degree in aeronautics and astronautics from Purdue University. Prior to joining NASA, her work involved engineering and operations for deep-ocean research submersibles and robots—that prized “isolated, confined environment” the agency wants to see in applications. Outside of her core competencies, O’Hara is already skilled in private piloting, emergency medicine, and outdoor sports such as sailing, surfing, backpacking, and skiing.

We asked O’Hara four questions to learn more about becoming an astronaut and what to expect next.

1. What do you spend your training doing?

As O’Hara explains, the bulk of the basic training is learning how to spacewalk, or to perform activities in a spacesuit. Most of that training is done in a huge pool at NASA called the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory. The pool includes a full-scale model of much of the International Space Station, allowing astronauts to practice spacewalks in a floating water environment that is somewhat similar to weightlessness.

So how do you stand out from the others? NASA keeps its requirements very broad, in general, only requiring a relevant STEM (science, technology, engineering, or math) degree or some military experience.

But a typical astronaut’s resume has much more than a degree. They have accumulated experience in space-adjacent activities such as piloting, skydiving, or underwater diving. They spend years in what the industry terms “isolated, confined environments.” This can range from working on a ship or joining an expedition to Antarctica—the agency wants to see how one deals with dangerous situations and how one manages working on small teams. A background with government agencies is a huge plus, along with experience teaching the next generation.

Then there is also the luck factor, as astronauts often apply for multiple rounds before being accepted—if it happens at all. If you can’t make it to space, however, NASA has a lot of jobs available for qualified space fans, ranging from roles in mission control to work on its range of planetary missions. You can also pivot into the fast-growing space industry, work as a space educator, or continue as a hobbyist in fields such as astronomy.

O’Hara, however, managed to beat the odds through a combination of luck and experience. She earned a bachelor of science degree in aerospace engineering at the University of Kansas and a master of science degree in aeronautics and astronautics from Purdue University. Prior to joining NASA, her work involved engineering and operations for deep-ocean research submersibles and robots—that prized “isolated, confined environment” the agency wants to see in applications. Outside of her core competencies, O’Hara is already skilled in private piloting, emergency medicine, and outdoor sports such as sailing, surfing, backpacking, and skiing.

We asked O’Hara four questions to learn more about becoming an astronaut and what to expect next.

1. What do you spend your training doing?

As O’Hara explains, the bulk of the basic training is learning how to spacewalk, or to perform activities in a spacesuit. Most of that training is done in a huge pool at NASA called the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory. The pool includes a full-scale model of much of the International Space Station, allowing astronauts to practice spacewalks in a floating water environment that is somewhat similar to weightlessness.

Loral O’Hara completed two years of astronaut training. Photo Source: NASA

Key technical skills were also instilled in O’Hara’s astronaut group. These included flying the T-38 jet, a common jet plane used by NASA astronauts that teaches them how to deal with landings, takeoffs, adverse weather conditions, and the very occasional emergency. This training is key to staying safe in space, where things can change quickly.

She also learned Russian—one of the two official languages of the space station—and how to operate the robotic Canadarm2, which is used for spacewalks and for bringing cargo spacecrafts full of supplies to the space station.

“While those were the core areas of astronaut candidacy, we learned other things too,” she says. “We did basic training in geology, and had two weeks where we were out in the field with geologists, learning the basics. We also did a lot of expeditionary skills training, like National Outdoor Leadership School trips out in the wilderness that were geared towards learning to communicate better as a team. We both got the opportunity to be a leader and to be a part of a team, and to get feedback on things that are essential to the success of a space mission.”

2. Why are you excited about Artemis?

Coming back to her crewmates, O’Hara said she is in awe of the various women who have already been named to potential future Moon teams. Among them are people such as Christina Koch (who spent a year in space), Kate Rubins (the first person to sequence DNA in space), and Anne McClain (a talented military pilot who is the second known LGBTQ+ person to fly in space).

“I’m in awe of all those people,” O’Hara says. “More broadly, I think it’s important to—especially for kids—to see role models and people that look like them. When I was in high school, I got to meet Eileen Collins, the first female commander of the space shuttle. So having those role models was important to me, growing up. I think it’s an exciting development, and I’m excited to be a part of it. It could be that one of the women I work with will be the first to set foot on the Moon.”

O’Hara also mentioned that working in space is often the culmination of work over many decades; while the media focus on what the view looks like out the window, for the participating astronauts it’s a moment where they can deploy their research and skills accumulated over many years of training and supporting other missions.

3. What advice would you give to people wanting to explore icy moons, like Europa?

O’Hara’s work on deep-ocean robotic submarines like Alvin has given her some insight into future missions on Europa, near Jupiter. On Earth, she says, people are testing such robots “to help develop not just the scientific instrumentation, but new approaches to looking for life. These life forms in the deep ocean in no way resemble anything that we’re familiar with on the surface. They don’t need sunlight or oxygen and they are living off chemicals.”

The additional challenge at Europa, however, is that the ice is roughly 20 km thick and it would be difficult to probe through it to the ocean beneath. Once we drill through there, perhaps we might see in action a later-stage version of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory robot BRUIE (Buoyant Rover for Under-Ice Exploration). BRUIE can cling onto the underside of the ice to search for life. “We’re exploring what we should be putting on this Europa vehicle, and how we should be going about searching those oceans,” O’Hara explains.

4. Children frequently say they want to become astronauts when they grow up. What advice would you give a child?

O’Hara cautioned that being selected as an astronaut is not a spaceflight guarantee, at least at the flight rates we see today—although private companies may make space tourism more possible in the future. Instead, her message is about following your passions and finding a pathway that both includes space and also highlights your particular skills and talents.

She also learned Russian—one of the two official languages of the space station—and how to operate the robotic Canadarm2, which is used for spacewalks and for bringing cargo spacecrafts full of supplies to the space station.

“While those were the core areas of astronaut candidacy, we learned other things too,” she says. “We did basic training in geology, and had two weeks where we were out in the field with geologists, learning the basics. We also did a lot of expeditionary skills training, like National Outdoor Leadership School trips out in the wilderness that were geared towards learning to communicate better as a team. We both got the opportunity to be a leader and to be a part of a team, and to get feedback on things that are essential to the success of a space mission.”

2. Why are you excited about Artemis?

Coming back to her crewmates, O’Hara said she is in awe of the various women who have already been named to potential future Moon teams. Among them are people such as Christina Koch (who spent a year in space), Kate Rubins (the first person to sequence DNA in space), and Anne McClain (a talented military pilot who is the second known LGBTQ+ person to fly in space).

“I’m in awe of all those people,” O’Hara says. “More broadly, I think it’s important to—especially for kids—to see role models and people that look like them. When I was in high school, I got to meet Eileen Collins, the first female commander of the space shuttle. So having those role models was important to me, growing up. I think it’s an exciting development, and I’m excited to be a part of it. It could be that one of the women I work with will be the first to set foot on the Moon.”

O’Hara also mentioned that working in space is often the culmination of work over many decades; while the media focus on what the view looks like out the window, for the participating astronauts it’s a moment where they can deploy their research and skills accumulated over many years of training and supporting other missions.

3. What advice would you give to people wanting to explore icy moons, like Europa?

O’Hara’s work on deep-ocean robotic submarines like Alvin has given her some insight into future missions on Europa, near Jupiter. On Earth, she says, people are testing such robots “to help develop not just the scientific instrumentation, but new approaches to looking for life. These life forms in the deep ocean in no way resemble anything that we’re familiar with on the surface. They don’t need sunlight or oxygen and they are living off chemicals.”

The additional challenge at Europa, however, is that the ice is roughly 20 km thick and it would be difficult to probe through it to the ocean beneath. Once we drill through there, perhaps we might see in action a later-stage version of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory robot BRUIE (Buoyant Rover for Under-Ice Exploration). BRUIE can cling onto the underside of the ice to search for life. “We’re exploring what we should be putting on this Europa vehicle, and how we should be going about searching those oceans,” O’Hara explains.

4. Children frequently say they want to become astronauts when they grow up. What advice would you give a child?

O’Hara cautioned that being selected as an astronaut is not a spaceflight guarantee, at least at the flight rates we see today—although private companies may make space tourism more possible in the future. Instead, her message is about following your passions and finding a pathway that both includes space and also highlights your particular skills and talents.

Loral O’Hara worked as an engineer of underwater submersibles and is also a pilot. Photo Source: NASA

For her, working as an engineer on a major upgrade to the Alvin submersible checked those boxes—Alvin first came in service in the 1960s and has undergone several major upgrades since then. Along with learning how to work in a dangerous environment at sea, O’Hara says the experience taught her about “leadership and teamwork and communication, and peacefully coexisting with a group of people when you’re trying to do something really challenging. That was probably the most valuable thing I took away from it, rather than how to turn a wrench.”

As for her advice for young people: “Find what you’re passionate about and pursue that, while also being open to seeking out new and different experiences,” O’Hara says. “As you try different things and you meet different people, all of those things broaden your world and inspire you. These experiences teach you new things, or help you develop new skills. There’s also cross-pollination, where you are working on one thing, and you grab different ideas from other fields you’ve worked in. It’s hard to say ahead of time how you might adapt. So I would advise staying open to new things, and trying new things, and being curious about the world.”

As for her advice for young people: “Find what you’re passionate about and pursue that, while also being open to seeking out new and different experiences,” O’Hara says. “As you try different things and you meet different people, all of those things broaden your world and inspire you. These experiences teach you new things, or help you develop new skills. There’s also cross-pollination, where you are working on one thing, and you grab different ideas from other fields you’ve worked in. It’s hard to say ahead of time how you might adapt. So I would advise staying open to new things, and trying new things, and being curious about the world.”